Writing these pieces for WaterCraft does make me try to rationalise what I have been doing all these years. What was my approach to re-building and restoring old boats? What was the thought process? Why did I use certain materials? Who influenced the process and many other questions which have occupied time spent restoring boats. It is not until the editor says it time to write it down in a logical way that I have to think about it.

Over the last 40 years, there have been some important changes to the wooden boat world. Firstly, the notion of restoring, re-building and maintaining old wooden boats has blossomed. In my 'Thames world', the late Peter Freebody was inspirational and trend setting from his remarkable boatyard at Hurley which to this day is the gold standard for fine wooden boatbuilding on the river. He was restoring beautiful launches while the might of the GRP revolution was gathering pace in the late 1960s and all through the 70s.

Secondly, the re-incarnation of electric propulsion afloat has been a game changer. The first iteration of electrically powered boats was back in the 1880s up until the First World War when petrol engines were becoming well developed and everyone abandoned steam and electric to embrace the internal combustion engine. Modern electric propulsion systems are quiet, smooth, reliable and very environmentally friendly.

Peter Freebody and friends, taking it all in at the Thames Traditional Boat Rally in Henley on Thames.

Thirdly, the ubiquitous epoxy brought about new techniques and construction methods which coupled with boat design changing from pen on paper to Computer Assisted Design - CAD – software leading to accurate Computer Numerically Controlled – CNC - cutting of hull moulds and patterns, making it far easier to set up to build a boat.

Lastly, information is now widely and easily shared through modern communication and technology, which is how the cult of epoxy has become the go-to standard adhesive, filler, sheathing bonder, coating and general boatyard 'cure for all ills'.

As a working boatbuilder, there are a few external influences which inform various decisions and choices, not least the customer's budget and preferences. Part of delivering a successful project is understanding the approach to future maintenance, particularly the choices of finishes. Obviously, there is a cost in caring for a wooden boat but maintenance is not such a familiar practice to busy modern owners. The result is opting for finishes you might prefer not to use but ones which will last longer and cope with neglect.

Analysing my own approach to restoring wooden boats, in no particular order, it goes like this. Faced with a beautiful 100-year-old carvel planked launch in need of a significant restoration, my first thought is that I must enable this boat to last another 100 years. This might seem a silly reaction as I have no hope of influencing the care of this boat for that length of time. However, it is a valid and responsible starting point even if the budget will not run to re-planking in teak. Removing rot is a given, as is choosing the right materials, appropriate finishes, considering ventilation and many other boat-life enhancing decisions.

Saving original material and replacing the un-saveable by matching material and design where possible retains the history of the boat and honours those who first built her. An example is the wonderful beaded edge moulding often found in bulkhead match boarding or head linings made originally using a wooden moulding plane. Call me a Luddite but I will always go to the moulding plane which makes its distinctive bead rather than a tungsten cutter in an electric router producing a perfect radius.

As a comparison with another trade, vintage car restorers are a dedicated sub-culture who go to great trouble to maintain originality; they would never fit a 1928 4½ litre Bentley with wide alloy wheels. Restoring is about retaining the look, feel and genuine character of the boat, not, in my view, modernising it with inappropriate materials, fittings and design excesses.

Still with their place in the wooden boat builder's toolbox: traditional moulding planes for edge decoration.

Plywood can have its place in a restoration project. Of course, the best plywood is a uniform consistent material, though it can never match solid wood in appearance or feel. I have used it as a structural core in bulkheads panelled over with traditional joinery or match boarding. Plywood sub-decks are common practice as they give watertight structural strength and reduce the quantity of expensive teak.

Personally, although I have used this construction with an epoxy bonded sheathing protecting the ply, I am not comfortable with bonding the deck planking directly onto the ply, having replaced a few decks where the caulking has failed and water has soaked into the ply resulting in a soggy mess. Tight fitted plywood floors or sole boards are some of my bête noires in old boat restoration. It’s not just the modern look of plywood, my real objection is that it eliminates good ventilation through the bilge.

Understanding epoxy is critical to a successful outcome. The ability of epoxy to bond to timber and effectively seal it against changes in moisture content are well known. Used as a very effective primer to stabilise topside planking enabling a high quality, long lasting two pack polyurethane paint finish is a very useful technique that I have used on many restorations.

Modern methods also have their place. Above: Replacing a traditionally made stem assembly, made up of five different pieces of timber bolted together in different grain orientations, with just two epoxy-laminated components with the grain of both following the stem profile.

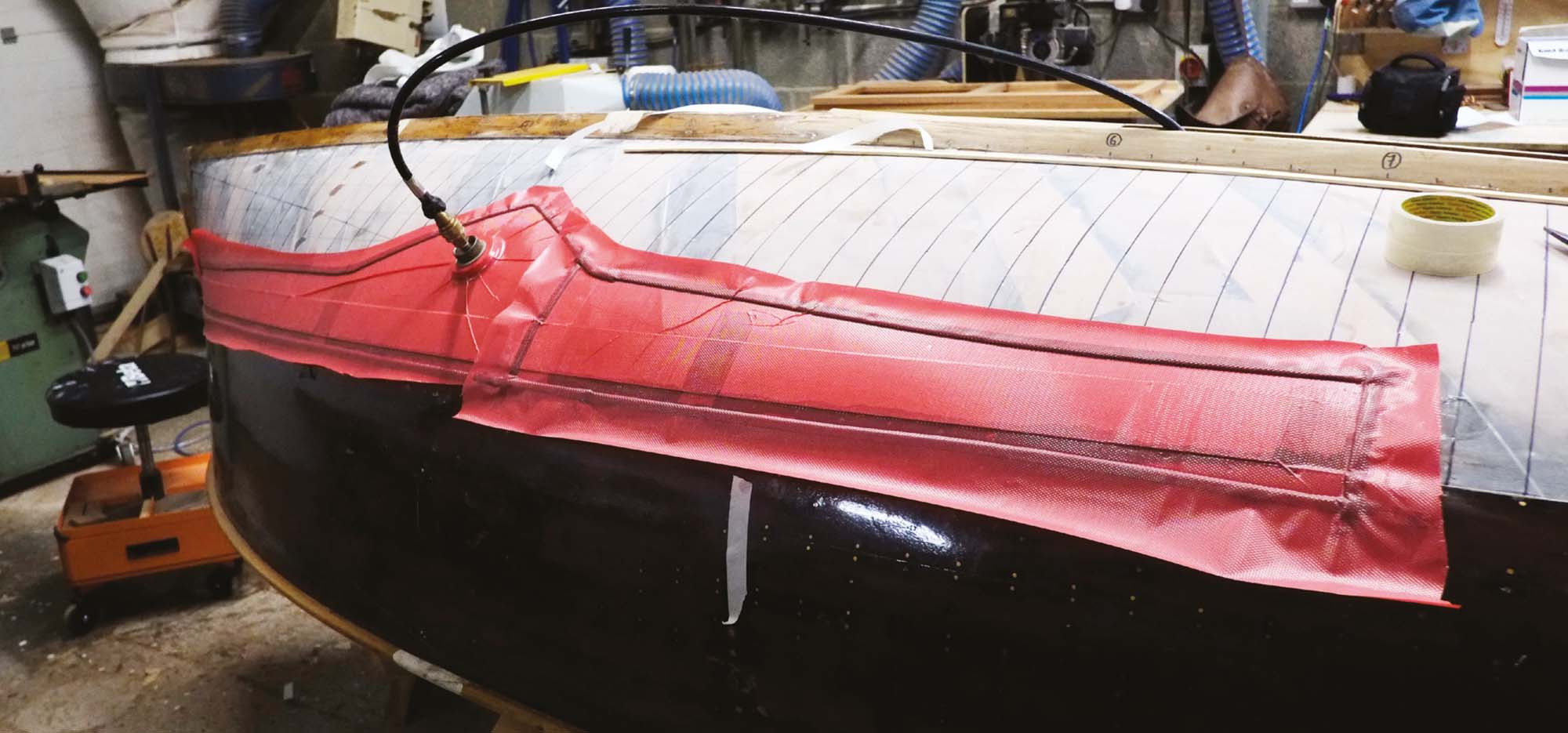

Below: Instead of calico – which rots – between the skins of this cold-moulded hull, the surface was epoxy-glass sheathed and the fore-and aft outer skin fitted using vacuum-bagging to ensure an airtight fit.

To my mind, clear coating using epoxy never really works for restoration projects and I avoid it; the look is gin clear and does nothing for the appearance of the timber in the way a tung oil rich varnish enhances the colour. Epoxy is very sensitive to ultra violet degradation and has to be well protected with two pack polyurethane varnish; if it is allowed to deteriorate it is a tedious task to scrape back the yellowed epoxy.

Using epoxy coating below the waterline on traditionally constructed hulls is, in my opinion, a path that will lead to problems. It is easy enough to coat the outside, given sound, dry planking but impossible to completely encapsulate each component of the structure on the inside. Any water which accumulates in the bilge will, inevitably, encourage the timber to expand without the safety valve of caulked seams to relieve the pressure of the swelling putting great strain on fastenings and framing.

There is always an exception to a rule: I have used epoxy sheathing and bonding on a few early multi-skinned International 14 sailing dinghies where I have re-planked below the waterline Once the inner diagonal layer of planking was repaired, the surface was epoxy sheathed rather than replacing the calico originally used between the layers. The fore and aft outer planking was then bonded to the sheathing and its outer surface also sheathed up to the waterline and painted. These boats are always dry-sailed and beautifully cared for, the modern epoxy materials are not visible and the hull is considerably stronger as a result.

Gone are the days when timber yards stocked grown oak bends, known as crooks, for knees, frames and stems. So laminating structural curved components from 'sandwiches' of thin layers of timber glued together with epoxy adhesive and protecting the structure with impermeable epoxy primers is a good solution.

Replacing a stem apron, forefoot and stem structure is fiddly in the extreme. The original assembly could be in four or five pieces all scarfed and bolted together, with the grain running in different directions. Laminating the whole structure brings the number of components down to two – the apron and the stem/forefoot – with only the scarf joints linking it onto the hog and keel to contend with. There is also a consistent grain direction running around the curve making cutting the plank rabbet a doddle. It is essential the structure is protected with epoxy primer and a well fitted metal banding on the leading edge.

Installing modern electric propulsion systems will transform a launch that was once powered by an internal combustion engine. Disguising the installation of the equipment is not difficult, the electronic control equipment and charger can be hidden in a well ventilated locker and in an ideal set-up, the batteries can be under the floor. The motor control lever requires a bit of imagination to eliminate the plastic and chrome of the off-the-shelf unit and the instrumentation can be kept to a minimum with only an old fashioned ammeter on open display.

Of course, with electric propulsion there is no need to turn on fuel, water intakes or bilge blowers, just a key switch, move the 'throttle' just a little and you are off. The simplicity of the whole system is beautiful.

Others might disagree with this restorer’s approach; this is my version but there are as many alternative ways as there are points of view on how to keep an old boat original and useable. The key to success is understanding the heritage of the boat, the different materials involved and exactly how they are put together.

Instead of a bulky midships box for a petrol engine, this unobtrusive and stylish housing hides an electric propulsion plant. Boatbuilders have enough deadlines in their lives; Colin will be taking a brief sabbatical and resume his Log in the autumn.